Overview

Abstract

The Nervous System is a preliminary system that will represent the central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral nervous system (PNS). Currently, the system includes a baroreceptor feedback model that is used to regulate arterial pressure. This is accomplished by tracking the normalized changes in important cardiovascular circuit parameters, such as heart rate, vascular resistance, and vascular compliance. The normalized changes are communicated to the Cardiovascular System, where they are adjusted in an attempt to return arterial pressure to its normal value. The model was validated with an acute hemorrhage scenario. The baroreceptor feedback shows good agreement with the expected trends. Additionally, the Nervous System provides for the tracking of intracranial pressure and cerebral blood flow for examination in traumatic brain injury events and pupillary size and reactivity for brain injuries and drug effects. In the future, other feedback mechanisms will be added for both homeostasis or crisis states.

Introduction

The Nervous System in the human body is comprised of the central nervous system (CNS) and the the peripheral nervous system (PNS). The CNS contains the brain and the spinal cord, while the PNS is subdivided into the somatic, autonomic, and enteric nervous systems. The somatic system controls voluntary movement. The autonomic nervous system is further subdivided into the parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous system. The sympathetic nervous system is activated in times of stress and crisis, commonly referred to as the "flight or fight" behaviors. The parasympathetic nervous system controls homeostasis functions during the relaxed state. The enteric nervous system controls the gastrointestinal system. Many of these behaviors are tightly connected to the Endocrine System. In many cases, the Nervous System receptors trigger hormone releases that cause systemic changes, such as dilation and constriction of vessels, heart contractility changes, and respiration changes [152].

The engine will focus on a select few mechanisms within the Nervous System to provide feedback for both homeostasis and crisis behavior in the body. The list is shown below:

- Baroreceptors

- Chemoreceptors

- Local autoregulation

- Temperature Effects

- Generic parasympathetic and sympathetic effects

Additionally, the engine will model the following features related to brain function:

- Simple model of traumatic brain injury (TBI)

- Intracranial pressure

- Pupillary response to drugs and TBI

System Design

Background and Scope

Baroreceptor Feedback

The baroreceptor mechanism provides rapid negative feedback control of arterial pressure. A drop in arterial pressure is sensed by the baroreceptors and leads to an increase in heart rate, heart elastance, and a decrease in systemic vascular resistance. These changes operate with the goal maintaining arterial pressure at its healthy resting level. The baroreceptor mechanism may be divided into three parts: afferent, CNS, and efferent. The afferent part contains the receptors, which detect changes in the MAP. After that, the CNS portions the response into either sympathetic or parasympathetic. Lastly, the efferent part is used to provide feedback to the vasculature and organs within the Cardiovascular System [275]. The model chosen only models the CNS and efferent portion of the baroreceptors. The fidelity of the model does require the modeling of the actual stretch receptors in the aorta or carotid arteries to provide the necessary feedback. Instead the changes in MAP are used to calculate changes in parasympathetic and sympathetic responses, which trigger the changes in the Cardiovascular System.

TBI

Traumatic brain injuries are relatively common, affecting millions annually. They are usually defined as a blunt or penetrating injury to the head that disrupts normal brain function. Furthermore, they are classified as either focal (e.g. cerebral contusions, lacerations, and hematomas) or diffuse (e.g. concussions and diffuse axonal injuries) [7]. The scope of the TBI model is somewhat limited by the low fidelity of the modeled brain. The brain is represented in the current Cardiovascular circuit with only two resistors and a compliance, all within one compartment. Because the circuit is modeled in this way, TBI is considered as an acute, non-localized, non-penetrating injury from a circuit perspective. Thus, the TBI model can account for intracranial pressure and cerebral blood flow on the basis of the whole brain, but not to specific areas of the brain. However, the engine does provide for three injury inputs: diffuse, right focal, and left focal. These will be discussed in the Actions section. Similarly to the Renal System, the brain circuit could be expanded to accommodate a higher-fidelity brain model.

Pupillary Response

The pupil is the small hole in the iris that allows light to pass through the lens, allowing vision. The pupil's diameter is controlled by the autonomic nervous system in order to affect the amount of light entering the eye. This diameter control is carried out by two muscles: the pupilloconstrictor, which is parasympathetically controlled (via the neurotransmitter acetylcholine), and the pupillodilator, which is sympathetically controlled (via the neurotransmitter norepinephrine) [7]. The synaptic pathways for these two pupil effects differ, and thus, any deviation from normal pupil behavior can shed light on any interference, whether that be a brain injury causing increased pressure on a nerve or a drug effect interfering with synaptic transmission. Because pupil examination is informative yet minimally invasive, it is an excellent tool for helping to diagnose neurological problems. The PERRLA assessment is commonly used to classify pupillary behavior: Pupils Equal, Round, Reactive to Light, and Accomodating. Pupillary response is modeled by tracking any modification to pupil size and light reactivity for each eye. Both TBI actions and drugs can apply modifiers to pupil size and reactivity.

Data Flow

Initialization and Stabilization

The engine initialization and stabilization is described in detail in the stabilization section of the System Methodology report. The mean arterial pressure set-point is updated after the Cardiovascular system reaches a homeostatic state.

Preprocess

Baroreceptor Feedback

The baroreceptor feedback is calculated here. It calculates the difference between the current MAP and the recorded set point to determine modifiers for the important cardiovascular circuit parameters (heart rate, heart elastance, systemic resistance, and venous compliance).

Process

Check Brain Status

Intracranial pressure is checked here to determine whether or not to throw the Intracranial Hypertension or Intracranial Hypotension events.

SetPupilEffects

Pupil modifiers are retrieved from the Drugs System and combined with any modifiers from TBI before being applied to the eyes.

Post Process

There is no system specific functionality for the Nervous System in Post Process.

Assessments

Assessments are data collected and packaged to resemble a report or analysis that might be ordered by a physician. No assessments are associated with the Nervous System.

Features, Capabilities, and Dependencies

Baroreceptors

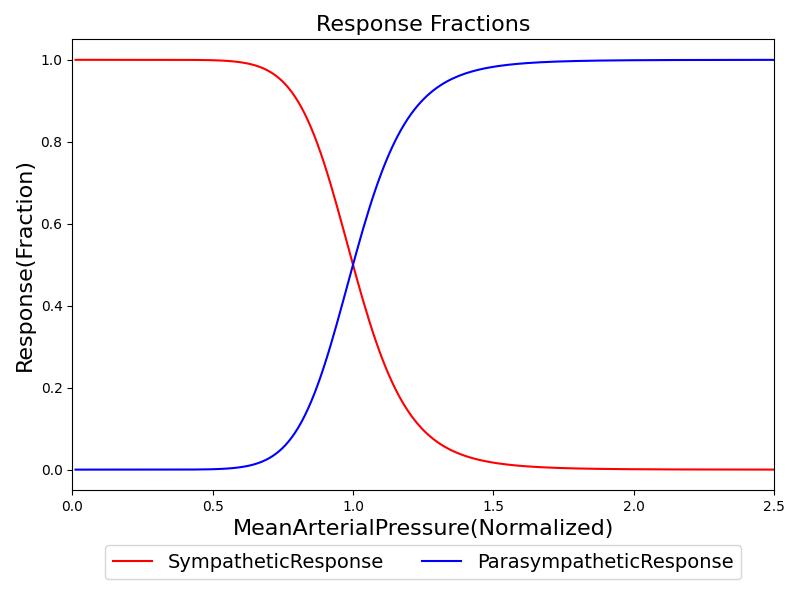

The baroreceptor model implemented is adapted from the models described by Ottesen et al [275]. The model is used to drive the current MAP towards the resting set-point of the patient. This is accomplished by calculating the sympathetic and parasympathetic response. The fraction of the baroreceptor response that corresponds to the sympathetic effects is determined from Equation 1. The parsympathetic fraction is shown in Equation 2.

![]()

![]()

Where ν is a parameter that represents the response slope of the baroreceptors, pa is the current MAP, and pa,setpoint is the MAP set-point. An example of the sympathetic and parasympathetic responses as a function of MAP are shown in Figure 1. These were calculated with an assumed MAP set-point of 87 mmHg. The model in [275] uses an &nu value of 1, which worked well in an isolated system. However, when integrated into the whole-body physiology model, this was unable to account for the accumulated response of the baroreceptors. For example, as the MAP increases, the sympathetic response increases, however, the effects of the sympathetic response drop the MAP. At the next time step, the sympathetic response will drop. In reality the response is required to maintain this effect, but the constant loop of feedback obscures the needed sympathetic response. To combat this, we increased the value of &nu to 4.

As described in the cardiovascular methodology report, the cardiovascular system is initialized according to patient definitions and the stabilized to a homeostatic state. The set-point is the resultant mean arterial pressure following the engine stabilization period. The set-point is adjusted dynamically with certain actions and insults, as shown in Equation 3.

![]()

Where Δpa,drugs and Δpa,exercise are changes in MAP due to drugs and exercise, respectively.

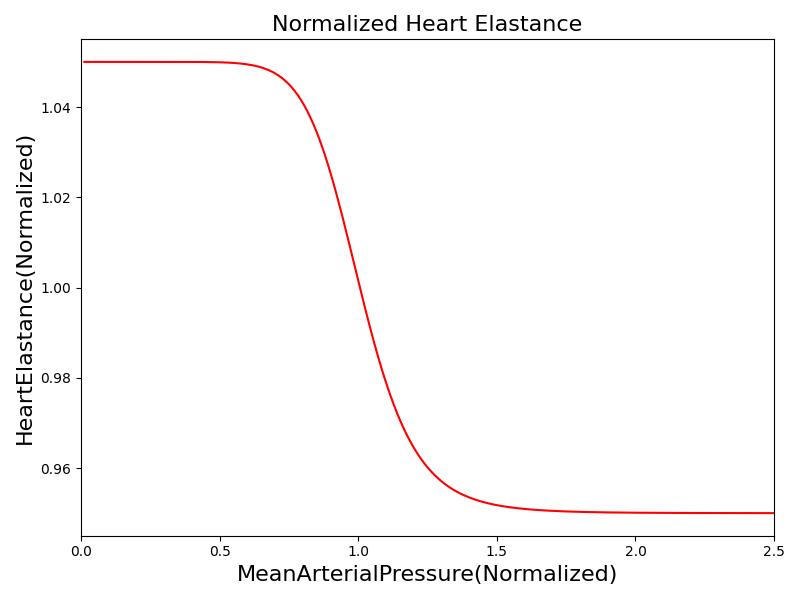

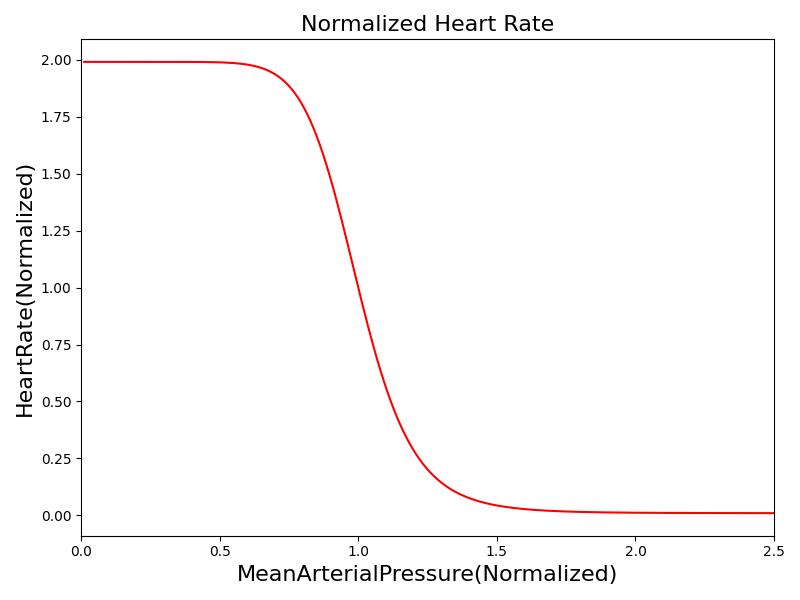

The sympathetic and parasympathetic fractional responses are used to determine the response of the following cardiovascular parameters:

- heart rate

- heart elastance

- systemic vascular resistance

- systemic vascular compliance This is accomplished by tracking the time-dependent values of each parameter relative to their value at the MAP set-point. The time-dependent behavior of these parameters is presented via a set of ordinary differential equations, as shown in Equation 4 - Equation 7.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

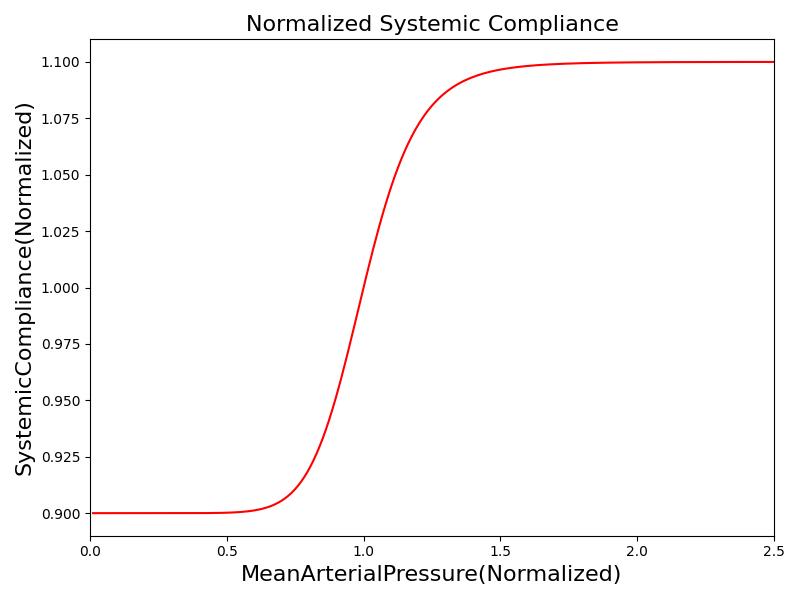

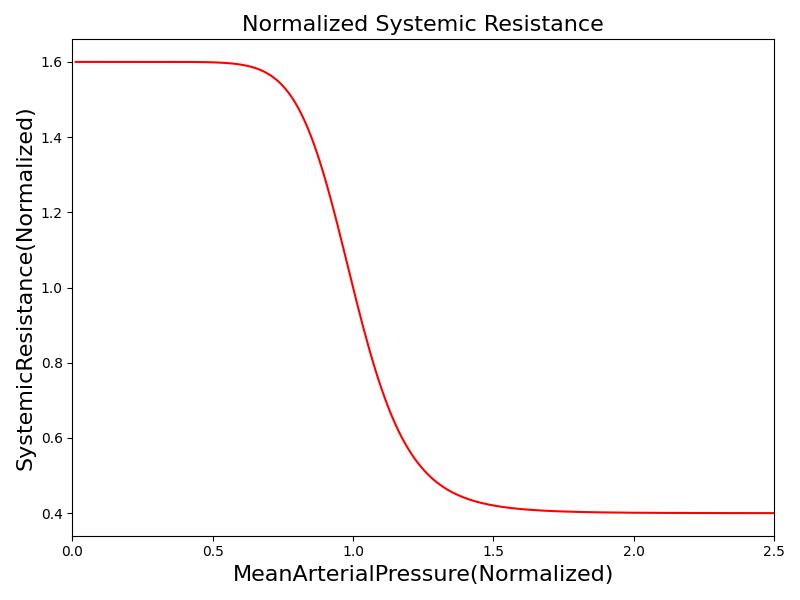

Where xHR, xE, xR and xC are the relative values of heart rate, heart elastance, vascular resistance and vascular compliance, respectively. τHR, τE, τR and τC are the time constants for heart rate, heart elastance, vascular resistance and vascular compliance, respectively. The remaining α, β and γ parameters are a set of tuning variables used to achieve the correct responses in the Cardiovascular System during arterial pressure shifts. Note that the heart rate feedback is a function of both the sympathetic response and parasympathetic response, whereas the elastance feedback and vascular tone feedback depend on the sympathetic or parasympathetic responses individually. Figure 2 shows the normalized response curves.

|

|

|

|

This model works well for smaller increases in MAP. However, the baroreceptors reach a saturation level and can no longer continue to apply the same level of change to the achieve a MAP response. This can be seen in the case of hemorrhage. Lower levels of hemorrhage result in the ability to fully maintain MAP with the above changes to parameters to the Cardiovascular System. However, as the blood pressure continues to drop, the baroreceptors become less effective. To account for this, the model includes a saturation parameter. When the sympathetic response reaches 0.78, an event is triggered for baroreceptor saturation. After the baroreceptors reach saturation, Equation 4 - Equation 7 are scaled to by a baroreceptor effectiveness parameter to reduce the response. When the MAP reaches a level of approximately 45 mmHg, the body responds with a "last-ditch" response. This is a strong burst of baroreceptor activity to attempt to sustain cardiovasclar function [152]. The baroreceptor effectiveness parameter is increased for a MAP between 40 and 45 mmHg to represent this response. Below 40mmHg, the baroreceptor effectiveness rapidly falls contributing to cardiovascular collapse. The best example of this response is the baroreceptor role in hemorrhage, particularly the role in the cascade to through hemorrhagic (hypovolemic) shock [152] [25].

It is also important to consider the second order effects of the baroreceptor response. The literature shows that the baroreceptors become less effective not only as the MAP deviates further from its baseline, but also as the response extends through time [337] [90], [71]. This sustained response is not feasible for long periods of time and barorector resetting occurs. A Baroreceptor Active event is triggered when the pressure diviates from the setpoint by plus or minus 5%. After 7 minutes of continuous baroreceptor activation, the MAP setpoint is modified in the direction of the diviation by 35% of the deviation. This is key for modeling longer scenarios where compensatory mechanisms begin to fail.

Chemoreceptors

The chemoreceptors are chemosensitive cells that are sensitive to reduced oxygen and excess carbon dioxide. Excitation of the chemoreceptors stimulates the sympathetic nervous system. The chemoreceptors contribute significantly to the control of respiratory function, and they are included in the respiratory control model developed. As sympathetic activators, the chemoreceptors also increase the heart rate and contractility. The complete mechanisms of chemoreceptor feedback are complicated and beyond the current scope of the engine, so a phenomenological model was developed to elicit an appropriate response to hypoxia and hypercapnia. Only the heart rate effects of chemoreceptor stimulation are modeled in the current version of the engine, but contractility modification will be included in a future release. Figure 3 shows the chemoreceptor effect on heart rate. In the figure, the abscissa values represent a fractional deviation of gas concentration from baseline, and the ordinate values show the resultant change in heart rate as a fraction of the baseline heart rate. The final heart rate modification due to chemoreceptors is the sum of the oxygen and carbon dioxide effects. For example, severe hypoxia and severe hypercapnia will result in a three-fold increase in heart rate (baseline + 2 * baseline).

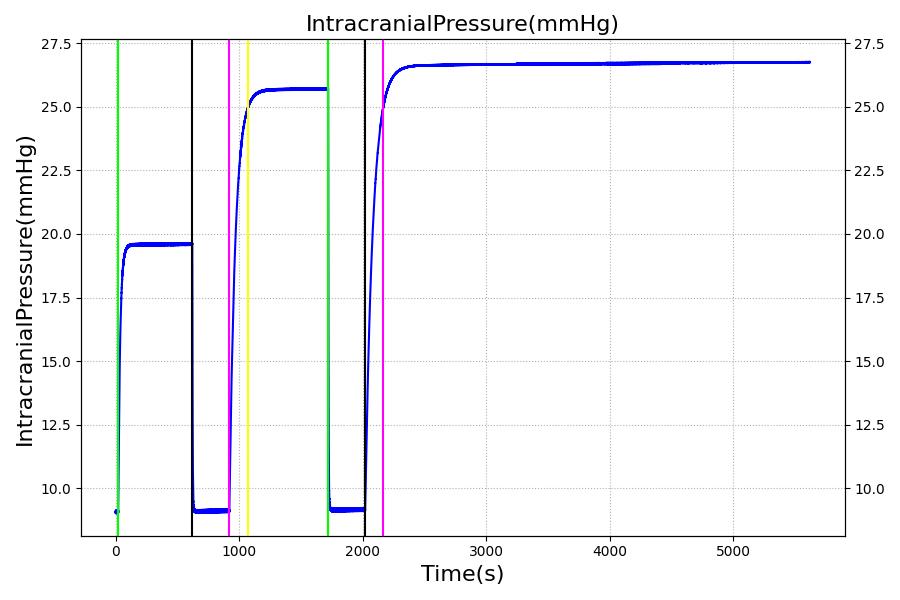

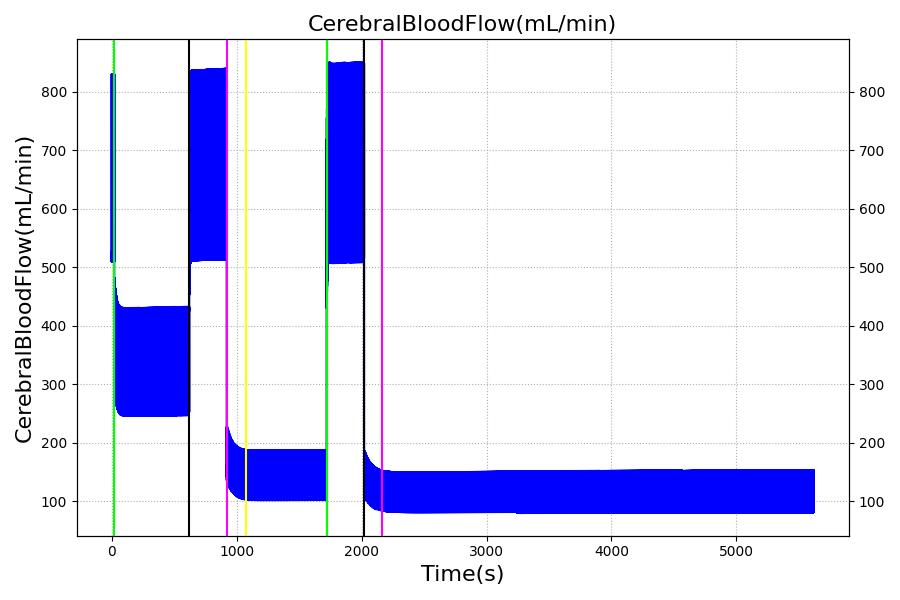

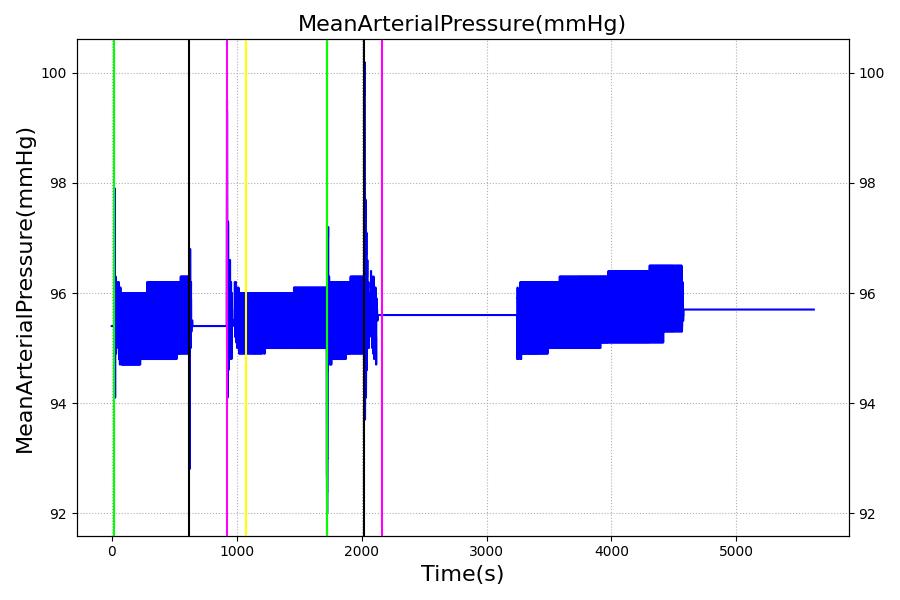

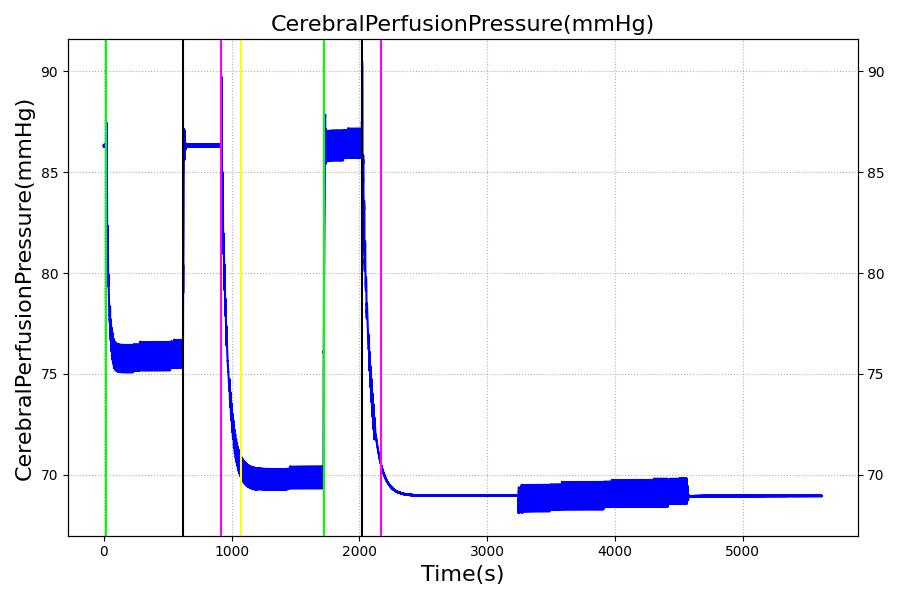

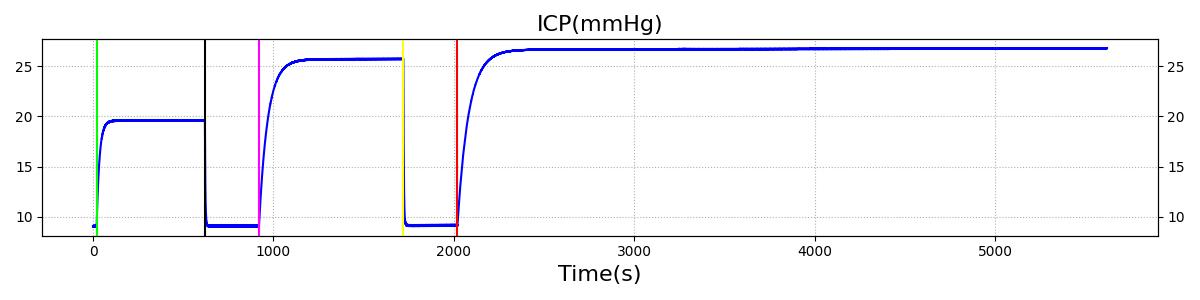

TBI

Three important metrics are used to evaluate patients with traumatic brain injuries: intracranial pressure (ICP), cerebral blood flow (CBF), and cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP). Patients with brain injuries often exhibit increased intracranial pressure, decreased cerebral blood flow, and a cerebral perfusion pressure outside of a normal range [349]. Cerebral perfusion pressure is defined as

![]()

Where MAP is the mean arterial pressure. In order to model these behaviors, the Brain Injury action will modify the resistors of the brain circuit, which is shown in Figure 4 below. The brain circuit is a section of the cardiovascular circuit.

By increasing R1 and R2, the ICP can be increased while CBF decreases. The resistors are tuned based on the severity (on a scale from 0 to 1) of TBI such that ICP is above 25 mmHg and CBF is near 8 mL per 100 grams of brain tissue per minute for the most severe injury.

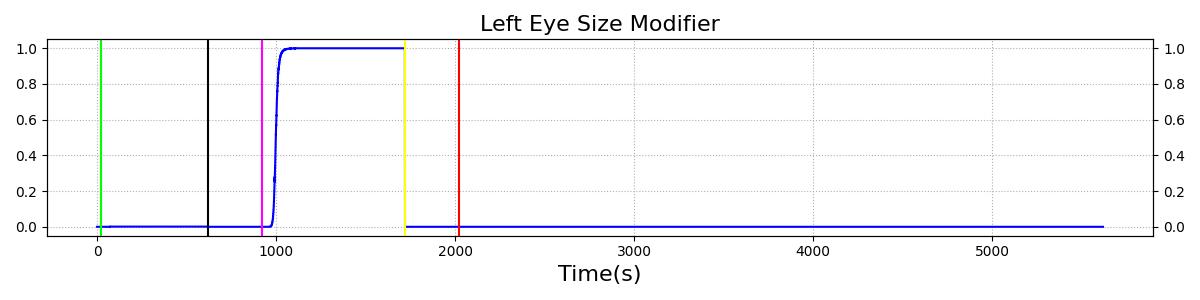

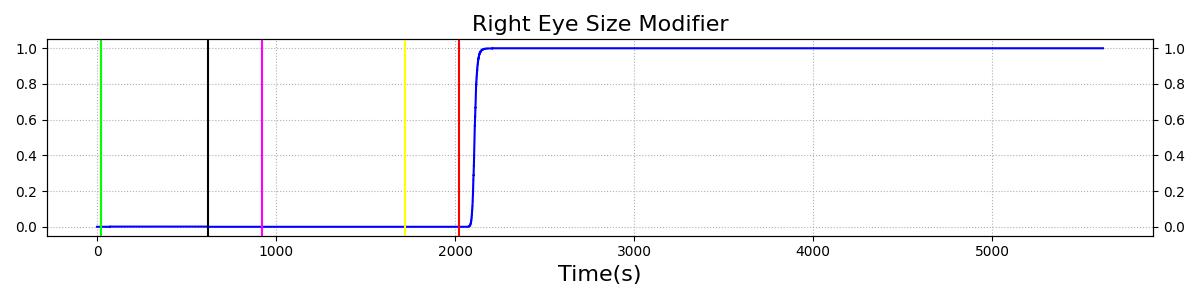

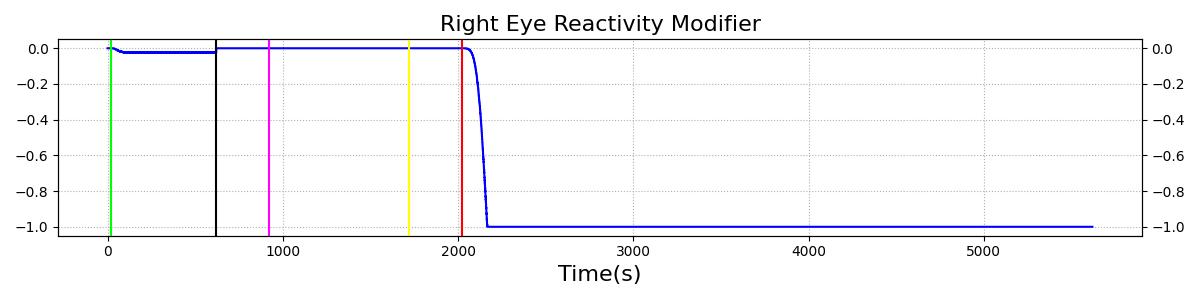

Pupillary Response

Pupil size and reactivity can vary patient-to-patient based on many factors, including age, mental and emotional state, and ambient light conditions [403]. Furthermore, pupillary assessments like PERRLA are often qualitative rather than quantitative. Because of this, the engine models pupillary modifiers rather than discrete pupil sizes and size changes over time. In this way, the pupillary effects can be assessed qualitatively without the need for baseline patient values for pupil size and reactivity.

There are two ways to affect the pupils in engine: drug pharmacodynamic effects and TBI. For a discussion of pharmacodynamic effects on pupillary response, see Drugs Methodology. The other method of influencing pupillary response is TBI. Increasing intracranial pressures constrict ocular nerves, causing pupillary disruptions [197]. Because of this relationship between ICP and pupil effects, ICP is the metric on which pupillary modifiers are based. For the pupil size modifier, Equation 9 was developed so that pupil size (ms) begins to see effects when ICP increases above around 20 mmHg, the pressure at which recoverable brain damage is often observed [349], hitting its maximum slope at 22.5 mmHg, and leveling off as ICP approaches 25 mmHg. For pupil light reactivity (mr, the curve seen in Equation 10 was developed so that it remains at 0 until ICP approaches 20 mmHg, then drops off sharply towards -1 as ICP approaches 25 mmHg. For both of these modifiers, a 1 represents "maximal" effect, -1 represents "minimal" effect, and 0 represents no effect. So a pupil size modifier of 1 would mean the pupil size is at its maximum possible diameter.

![]()

![]()

For diffuse injuries, these modifiers are applied to both eyes. For focal injuries, the modifiers are applied to the eye on the same side as the injury, as this reflects the most common observed behavior [197].

Patient Variability

The baroreceptor reflex gains and time constants are independent of patient configuration. However, set-points are computed after stabilization, and the baroreceptor reflex drives towards a configuration-specific homeostasis. Because TBI uses multiplicative factors to modify the brain section of the cardiovascular circuit, the patient variability of TBI is the same as that seen in the Cardiovascular System. There is no patient variability inherent in the pupillary response model, as it uses modifiers instead of baseline values. A detailed discussion of patient configuration and variability is available in the Patient Methodology report.

Dependencies

The baroreceptors interact directly with the cardiovascular system by modifying cardiovascular circuit and heart driver parameters. These include heart rate, left and right heart elastance, systemic vascular resistance and systemic vascular compliance. The cardiovascular parameters are modified by first calculating the normalized change in the parameter. This normalized change is passed into the common data model (CDM) where the cardiovascular system may extract the change and then apply it locally as a fractional adjustment. The resultant hemodynamic changes feedback directly to the MAP, and the updated MAP is used by the Nervous system in the next time slice to compute new normalized baroreceptor effects. TBI also directly modifies the cardiovascular circuit, specifically both the upstream and downstream brain resistors. Finally, the Drugs system can contribute additional pupillary effects, that combine with possible TBI pupil effects via simple summation.

Assumptions and Limitations

The limitation of the baroreceptor model implemented is not tracking adjustments in unstressed volume. Currently the engine does not correctly represent the physiologic unstressed volume under resting conditions. Therefore, these changes to the unstressed volume cannot be reflected in the engine. This may be addressed in future releases of the engine.

The TBI model assumes an acute injury to the brain; chronic effects are not considered, and neither are consciousness assessments. The brain is considered to be one compartment and is not subdivided into discrete functional areas. This means that there is no circuit distinction between a diffuse TBI and a Left Focal TBI. The only difference between the TBI actions is the expected pupil effect. TBI metric validation assumes a supine adult. The current TBI model does not consider specific effects of CO2 saturation, O2 saturation, or blood pH on CBF.

Actions

Insults

Brain Injury

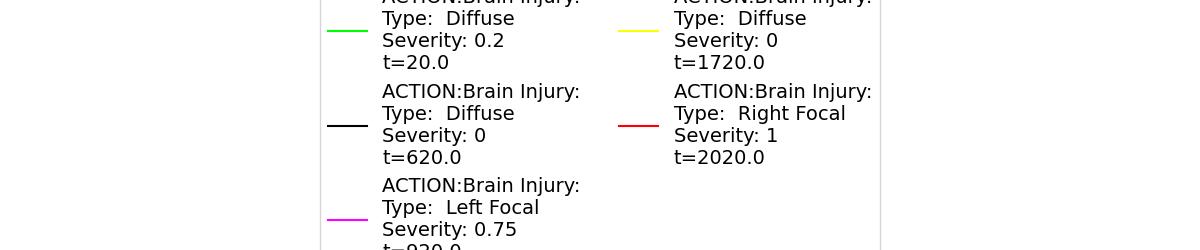

The Brain Injury action refers to an acute injury to the brain. Whereas in a real patient, a TBI could have manifold effects, both acute and chronic, the model only considers the effects of TBI on brain vascular resistance and pupillary response. The effects of the Brain Injury action depend on the severity value from 0 to 1 and a Type (Diffuse, Left Focal, or Right Focal) assigned to the injury. A severity of 0 will result in a multiplicative factor of 1 being applied to both the upstream and downstream resistors in the brain, which equates to no deviation from the normal, uninjured state. For an injury severity of 1, the upstream resistor is assigned a multiplicative factor of 4.775 and the downstream resistor is assigned a multiplicative factor of 30.409. Severity values between 0 and 1 are converted to multiplicative factors linearly. Increased flow resistance results in increased ICP and decreased CBF. A Diffuse-type injury affects both eyes equally, whereas a Left Focal injury affects only the left eye, and a Right Focal injury affects only the right eye.

Events

Intracranial Hypertension

Intracranial Hypertension is triggered when the intracranial pressure exceeds 25 mmHg. The event is reversed when the pressure returns below 24 mmHg.

Intracranial Hypertension

Intracranial Hypotension is triggered when the intracranial pressure drops below 7 mmHg. The event is reversed when the pressure returns above 7.5 mmHg.

Results and Conclusions

Validation - Resting Physiologic State

No resting state physiology validation was completed, because the baroreceptors do not provide feedback during the initial resting and chronic stabilization phases. For more information on the stabilization phases, see System Methodology.

Validation - Actions and Conditions

Actions and conditions with responses specific to the Nervous System were validated. A summary of this validation is shown in Table 1. More details on each individual scenario's validation can be found below.

| Key |

|---|

| Good agreement: correct trends or <10% deviation from expected |

| Some deviation: correct trend and/or <30% deviation from expected |

| Poor agreement: incorrect trends or >30% deviation from expected |

| Scenario | Description | Good | Decent | Bad |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baroreceptors | Patient has 10% blood loss in 30s. View response in heart rate, contractility, systemic vascular resistance, and venous compliance. | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Brain Injury (TBI) | Patient has three brain injuries of increasing severity with recovery in between. View response in intracranial pressure, cerebral blood flow, and cerebral perfusion pressure. | 23 | 2 | 0 |

| Total | 26 | 2 | 0 |

Baroreceptor Reflex

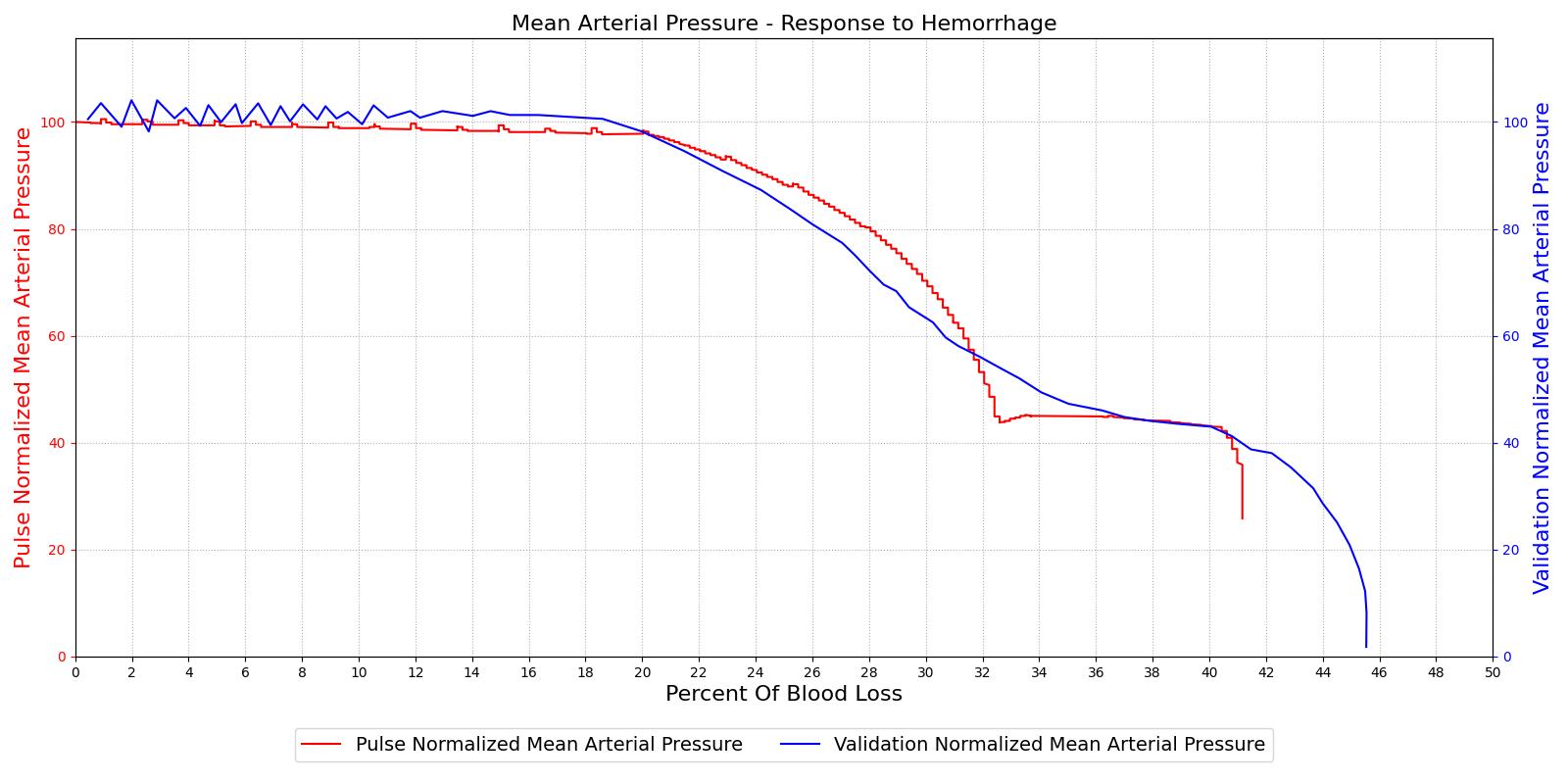

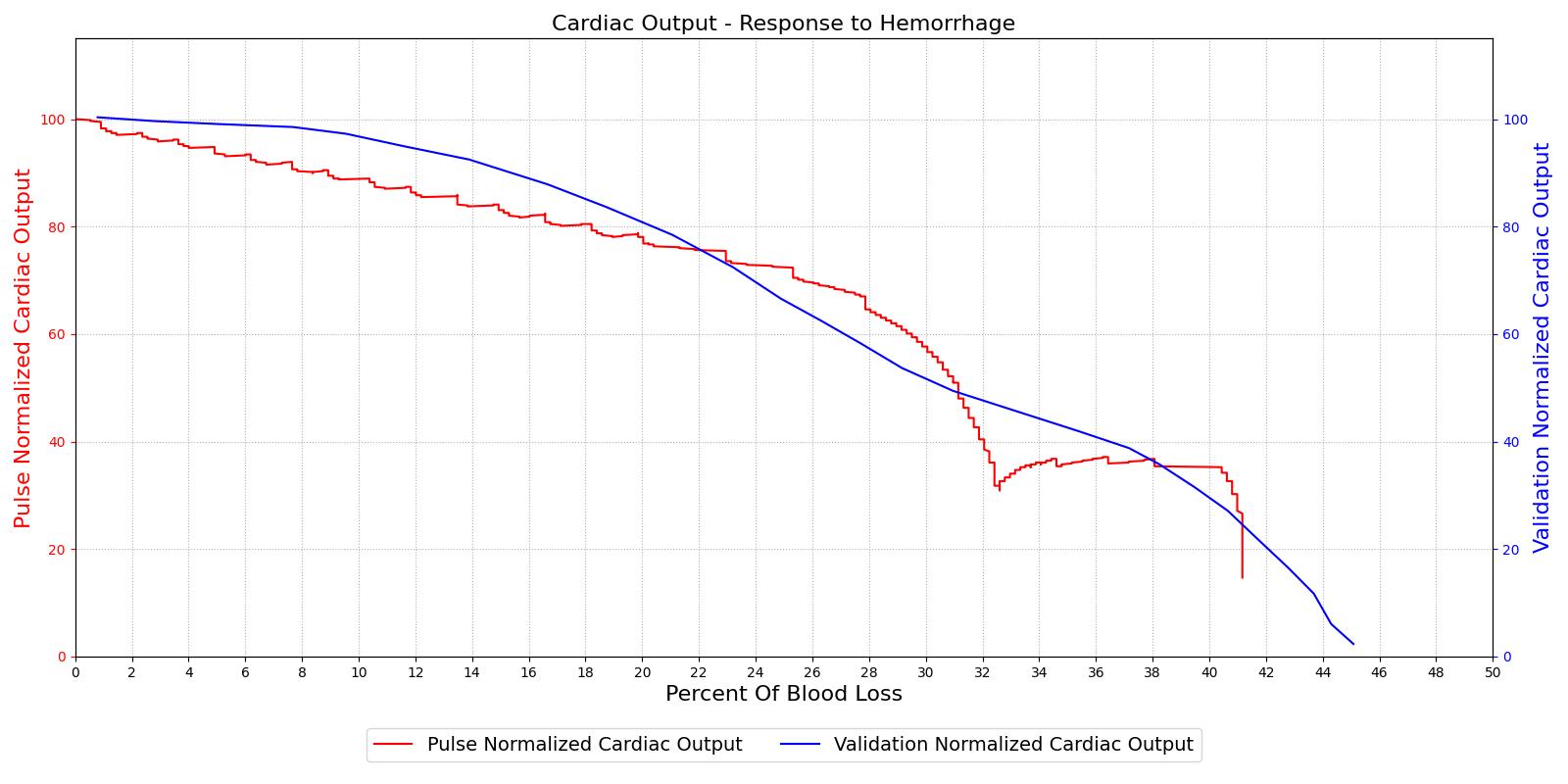

The baroreceptor reflex is validated through simulation of an acute hemorrhage scenario. This scenario begins with the healthy male patient. An hemorrhage is initiated and proceeds through hemorrhagic shock to patient death. The cardiac output and the MAP are shown in Figure 5 for both the Pulse model and the experimental data in [152]. This scenario and validation shows the baroreceptor activation and the effectiveness changes throughout the range of MAP changes important in hemorrhage. More details can be found in the @CardiovascularMethodology.

|

|

Table 2 The baroreceptor reflex validation data for the hemorrhage scenario shows good agreement with expected results.

| Action | Notes | Sampled Scenario Time (s) | Heart Rate (beats/min) | Cardiac Output (mL/min) | Systemic Vascular Resistance (mmHg s/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemorrhage | 10% blood loss in 30 s | 200 | Increase ~30% [154] [275] | Decrease ~15-20% [154] [275] | Increase 10-15% [154] [275] |

Brain Injury

The Brain Injury action is validated through repeated application and removal of increasing severities of TBI. The scenario begins with a healthy male patient. After a short time, a mild brain injury (Severity = 0.2, Type = Diffuse) is applied, and the patient is allowed to stabilize before the injury state is removed (only one TBI action can be in effect at a time, so adding a Diffuse Severity 0 TBI removes all TBI effects). This process is repeated for a more severe injury (Severity = 0.75, Type = Left Focal) and severe (Severity = 1, Type = Right Focal) brain injury. We expect to see increases in ICP, with the most severe injury resulting in an ICP greater than 25 mmHg, and decreases in CBF, with the most severe case approaching 8 mL per 100 grams of brain per minute, which, for the validated patient, equates to 108 mL per minute [241] [349]. The scenario shows good agreement for these values. We expect CPP to either increase above its maximum normal value or decrease below its minimum normal value, but, though we see a drop, it isn't quite as pronounced as expected [349]. We can also see that for the low severity injury, ICP doesn't quite reach the threshold to strongly affect the pupils. For the Left Focal injury, only the left pupil is affected, and for the Right Focal injury, only the right pupil is affected.

|

|

|

|

Table 3 The validation data for the TBI scenario shows good agreement with expected results.

| Action | Notes | Action Occurrence Time (s) | Sampled Scenario Time (s) | Intracranial Pressure (mmHg) | Cerebral Blood Flow (mL/min) | Cerebral Perfusion Pressure (mmHg) | Heart Rate (1/min) | Respiration Rate (1/min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brain Injury | Severity 0.2, CPP=MAP-ICP, StandardMale brain mass=1450g | 20 | 600 | 10% Increase [241] | Decrease [349] | Decrease [23] | 0-10% Decrease [241] | 0-10% Decrease [241] |

| Brain Injury | Severity 0 | 620 | 900 | 7-15 mmHg [349] | 50-65 mL/100g/min [152] | 60-98 mmHg | 72 [152] | [12.0, 20.0], [13.0, 19.0] [340] [234] |

| Brain Injury | Severity 0.75 | 920 | 1700 | Increase [349] | Decrease [349] | Decrease [23] | 0-15% Decrease [241] | 0-20% Decrease [241] |

| Brain Injury | Severity 0 | 1720 | 2000 | 7-15 mmHg [349] | 50-65 mL/100g/min [152] | 60-98 mmHg | 72 [152] | [12.0, 20.0], [13.0, 19.0] [340] [234] |

| Brain Injury | Severity 1 | 2020 | 3220 | >25 mmHg [349] | <8 mL/100g/min [349] | Decrease [23] | Decrease [241] | Decrease [241] |

Conclusions

The Nervous System is currently in a preliminary state that contains only a baroreceptor feedback model, basic TBI, pupillary response, and a chemoreceptor model. The baroreceptor feedback is used to control rapid changes in arterial pressure by adjusting heart rate, heart elastance, and vascular resistance and compliance. The baroreceptor model has been validated by comparing the engine outputs to experimental data for hemorrhage for both first order and second order responses. The unstressed volume changes are not accounted for in the model and may improve the performance of the model. The TBI model shows good agreement for the some basic TBI metrics for acute brain injuries. The introduction of an accurate ICP calculation based on cerebrospinal fluid properties will improve the model. Further discretization of the model will improve the localization of the TBI injury and effects. It is also important to include the damping of respiratory regulation as part of improving the TBI model. We also plan to improve the chemoreceptor model to include damping due to sedation and systemic vascular resistance and heart contractility changes. Pupillary response behaves as expected and arms the engine with yet another tool for matching output with clinical data.

Future Work

Coming Soon

- Chemoreceptor modification of heart contractility and systemic vascular resistance

- Local autoregulation

- Cerebrospinal fluid model

- Respiratory regulation damping with TBI and sedation

Recommended Improvements

- Including unstressed volume in the tone model

- Patient variability incorporated into the baroreceptor reflex model constants

- Cerebrospinal fluid model to calculate intracranial pressure

- Baroreceptor changes during exercise and sleep

- Positional variability

- Higher-fidelity brain model with localized injuries

- Interventions to treat TBI like drainage of cerebrospinal fluid, hypothermic treatment, hyperventilation, and mannitol therapy

- Consciousness model, including reduced level of consciousness with carbon monoxide and other intoxications

Appendices

Glossary

CBF - Cerebral Blood Flow

CNS - Central Nervous System

CPP - Cerebral Perfusion Pressure

ICP - Intracranial Pressure

PERRLA - Pupils Equal, Round, Reactive to Light, and Accommodating

PNS - Peripheral Nervous System

MAP - Mean Arterial Pressure

mmHg - Millimeters mercury